Many myths exist regarding weight training. For instance:

- Weight training will make you muscle-bound and inflexible.

- If you train with heavy weights and slow contractions, you’ll become heavy and slow.

- Squatting below parallel is an invitation for injury.

The list goes on.

None of these are entirely true. Weight training is simply a tool—it’s not the tool itself that should be blamed but rather how you use it. If you consistently train in a shortened range of motion (ROM), you may become muscle-bound and inflexible. If you always perform super-slow, volitional contractions, your athletic performance may not improve, and you could become slower. And yes, bouncing out of the bottom of a full squat is a recipe for injury.

But what if weight training is performed correctly? Can we put these myths to rest? Let’s find out.

Range of Motion: To Train Fully or Not?

A common area of confusion for many personal trainers is whether to train in full ROM or not. The answer? It depends on the individual and the joint in question. Generally, full ROM is encouraged—it’s how our joints are meant to move—but not always. A prime example is elbow or knee hyperextension.

If you ask a bodybuilder to extend their arms fully, you’ll often notice a slight state of flexion at the elbows. Ask a dancer to do the same, and you’ll typically see hyperextension. Both individuals could benefit from arm curls, but the way they perform the exercise should differ.

- A bodybuilder should take advantage of the passive stretch at the bottom position to restore any lost range and train in full ROM.

- A dancer, on the other hand, should avoid full extension at the elbow joint, stopping just shy of lockout to maintain joint integrity.

The same principle applies to the knee joint.

A good rule of thumb: If you train in poor posture, you’ll adopt poor posture. Similarly, if you train in a shortened ROM, you’ll adopt a shortened ROM—and vice versa.

Weight Training: A Powerful Flexibility Tool

Many people underestimate how effective weight training can be for improving flexibility and ROM. Olympic weightlifters, for example, are second only to gymnasts in flexibility. On the flip side, weight training can also decrease flexibility and ROM when used improperly.

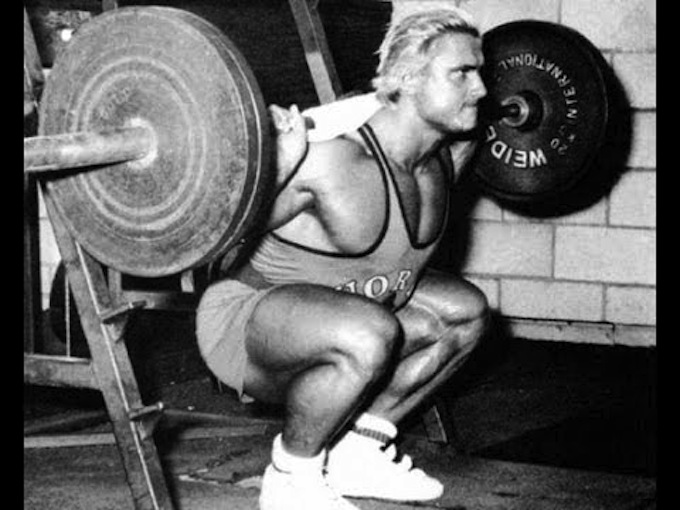

Take the stereotypical muscle-bound bodybuilder who constantly trains in a limited ROM. This can lead to shortened muscles and restricted movement. However, looks can be deceiving. Tom Platz, a professional bodybuilder known for his incredible leg development, routinely performed full squats. As a result, he had an impressive range of motion—able to touch his toes, place his head on his knees, and even do full splits. His famous saying still holds true: “Half squats will give you half legs!”

Most new clients struggle with full squats for several reasons:

- Tight calves cause the trunk to lean forward.

- Tight hip flexors make the heels lift.

- Tight glutes restrict squat depth.

- Tight hamstrings cause the lower back to round prematurely.

- A tight piriformis rotates the foot outward.

Over time, these limitations should be corrected, as a full squat is a natural and healthy movement.

The Stability-Mobility Continuum

When the ankle or hip joint is restricted in ROM, another joint compensates—usually the knees or lower back—leading to injury. Those who discourage full squats in favor of partial squats are actually increasing the risk of injury, not preventing it.

To help clients work toward a full squat, I use a method I learned from Dr. Mel Siff, which I call “potty training.” Using an adjustable step platform:

- Set the platform high and have the client squat onto it, then stand back up.

- Have them squat down again, brush the step, pause, and then return to standing.

- Repeat for the prescribed reps.

Over time, lower the step height until they can perform a full squat. Stretching tight muscles frequently will speed up this process.

Unilateral exercises, such as the split squat, are also beneficial. They help lengthen tight hip flexors, one of the most tonic muscle groups in the body. However, for most clients, the front foot should be elevated at first to allow for full ROM. Over time, the step height can be reduced until the exercise is performed on the floor—or even progressed with the rear foot elevated.

What If a Client Has Too Much Mobility?

Excessive joint mobility can be problematic. When a joint lacks stability, it becomes more prone to injury. In such cases, weight training can be used to decrease ROM strategically.

For hypermobile clients, I often prescribe a modified split squat with 90-degree bends at the knees. Instead of allowing the front knee to travel forward, the back knee moves straight down and lightly touches the floor before returning to the starting position. This shortens the ROM and provides much-needed joint stability.

Upper-Body Training: The Same Principles Apply

The belief that full ROM in pressing exercises, such as the bench press, will damage the shoulder joint is a myth—provided the exercise is done correctly. Newton’s Second Law states that force equals mass times acceleration. If speeds or loads are excessive, the risk of injury increases. But with proper form, a controlled tempo, and moderate loads, pressing in full ROM is safe.

In fact, avoiding full ROM can be harmful over time. Many people already present with rounded shoulders, and chronic pressing in a limited ROM can exacerbate this issue, leading to further postural deterioration. Pressing with full ROM and emphasizing the stretched position can counteract these effects.

A simple rule to follow: Stretch (lengthen) short, tight muscles, and strengthen (tighten) long, weak muscles.

Weight Training and Athletic Performance

Since the 1950s, research has consistently shown that weight training enhances athletic performance. Athletes have long understood its benefits, even without scientific validation. However, one area of ongoing debate is training speed.

Some believe that all concentric actions should be explosive, while others argue that it’s unnecessary. Science suggests that both perspectives have merit.

A 1993 study by David Behm and Digby Sale found that intended movement velocity—not actual velocity—determines the velocity-specific training response. In other words, even if a weight moves slowly due to its heaviness, the intent to lift it quickly is what matters for power development.

German research has further demonstrated that high-intensity weight training (1-3 reps with 90-100% of max strength) is superior for improving the rate of force development compared to lower-intensity training. Though the bar may not move fast, the key is to generate maximum force as quickly as possible.

The Bottom Line

It’s time to put weight training myths to rest. People want to train efficiently without wasting time, and weight training delivers the best return on investment.

- Yoga and stretching improve flexibility.

- Aerobic exercise enhances cardiovascular endurance.

- Pilates strengthens the core.

- Weight training does all of the above—and much more.

Forget the idea that lifting weights will make you heavy, slow, or inflexible. When used correctly, weight training is one of the most powerful tools for improving strength, flexibility, mobility, and athletic performance.

Stretching Smarter: The Do’s and Don’ts for Maximum Flexibility

By JP CatanzaroOriginally published: September 23, 2014 – Updated for 2025 Want to boost flexibility, prevent injuries, and optimize performance?

Training Economy: How Weight Training Can Be Your All-in-One Fitness Solution

Recent research has once again confirmed what many in the weightlifting community already know: weight training isn’t just for building

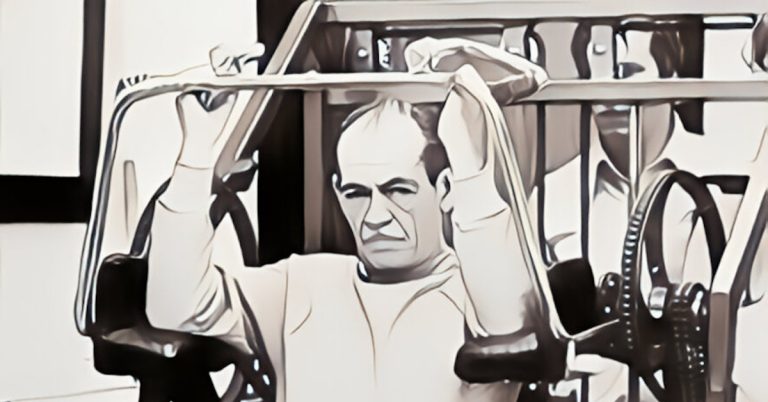

4 Invaluable Lessons from Strength Training Pioneer Arthur Jones

Arthur Jones, a true visionary in the realm of strength training, left an unforgettable mark on the fitness industry with

follow

Error: No feed with the ID 2 found.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.