As you hit your 40s, 50s, and beyond, you realize that you can’t do what you did in your teens, 20s, or even early 30s. Weights that once felt like feathers start feeling like boulders. Loads that used to be part of your warm-up sets suddenly become your working sets. It’s inevitable—just part of aging. But just because the loads may drop a bit doesn’t mean your strength and size have to plummet. You just need to train smarter, not necessarily harder!

When middle age hits, it’s time to follow moderate rules: use a moderately heavy weight, perform a moderate number of sets and reps, train at a moderate pace, and take moderate rest intervals. Sounds like a typical bodybuilding scheme, right?

So, you hit the gym with a plan—exercises, sequence, sets, reps, tempo, and rest intervals all mapped out in your training log. Everything looks perfect… on paper. But as soon as you start training, two key variables often get thrown out the window. You know which two.

Time Is More Important Than Load

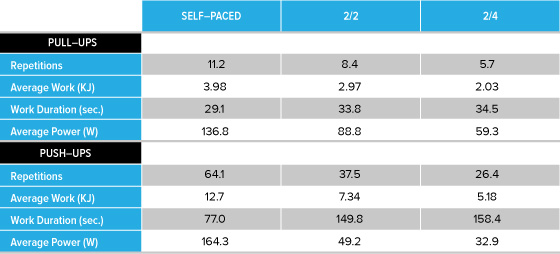

I had a revelation one day while reading a study by LaChance & Hortobagyi (1994) on exercise cadence. Researchers tested 75 moderately trained men on push-ups and pull-ups at different tempos: fast self-paced, 2/2 (2 seconds up, 2 seconds down), and 2/4 (2 seconds up, 4 seconds down). Faster cadences allowed for more reps, greater work, and higher power output.

If you only read the abstract, you’d think training at a self-paced cadence is superior. Not so fast—literally and figuratively!

When push-ups were performed at a 2/2 tempo instead of self-paced, reps were nearly cut in half, but time under tension more than doubled. A 2/4 cadence dropped reps even further but increased time under tension even more. A similar pattern was observed in pull-ups, though less dramatic.

(LaChance & Hortobagyi, 1994).

And why does time under tension matter?

The Science Behind Time Under Tension

A 1989 study in the Journal of Applied Sport Science Research analyzed muscle growth in cats (yes, cats). Researchers trained 62 cats five days per week for up to six years, using weighted wrist flexion. The results? The variable most correlated with muscle growth was lift time—not just the amount of weight lifted. Slow, controlled movements with heavy loads produced the greatest hypertrophy.

This was later confirmed in humans by Wernbom et al. (2007). Their massive 39-page review concluded that moderately heavy loads (70–85% of 1RM) yield the best hypertrophy results when sets are taken to near failure. It also suggested that total muscle activity per session is more important than total reps. As the paper states:

“The time-tension integral is a more important parameter than the mechanical work output (force x distance).”

The takeaway? You don’t need to train with maximal loads—just enough weight combined with sufficient time under tension.

How Much Tension and Duration?

For hypertrophy, the best range appears to be:

- Load: 70–85% of your 1RM (allowing for 5–12 reps max).

- Tempo: 4 to 6 seconds per rep.

- Time under tension per set: 20–72 seconds (e.g., 4 sec × 5 reps = 20 sec; 6 sec × 12 reps = 72 sec).

Sufficient, Not Complete, Recovery

Resting between sets is another key factor. Too little rest leads to excessive fatigue, but too much rest isn’t ideal either. You want sufficient, not complete, recovery.

Sufficient recovery occurs around the 3-minute mark. Waiting too long (5+ minutes) leads to a decline in neural activation, reducing performance on the next set (Young, 1992). Research also shows that moderate rest periods maximize anabolic hormone production.

Kraemer & Ratamess (2005) found that high-volume, moderate-intensity training with short rest intervals produces the greatest spikes in testosterone and growth hormone (GH). In fact, Häkkinen & Pakarinen (1993) showed that 10 sets of 10 reps at 70% 1RM with 3-minute rest intervals resulted in a twenty-fold increase in GH—similar to levels released during sleep.

Meanwhile, Robinson et al. (1995) and Willardson & Burkett (2006) confirmed that 3 minutes of rest allows for greater intensities, higher training volume, and greater strength gains.

It’s Better to Look Strong Than to Be Strong

Moderate rules apply to everyone, but they become essential as you age. As your tissues “dry out” and hormones decline, chasing maximal loads isn’t worth the risk of injury. A torn pec or wrecked back isn’t just an inconvenience when you’ve got a mortgage, a family, and a career.

Even Bill Kazmaier—one of the strongest men in history—has eased up over time. As he admitted to Iron Man’s John Rowley:

“When you get over 50, you’re better off looking strong than being strong!”

At the end of the day, no one at the beach cares how much you lift—they just care how you look. Young or old, it’s about time you follow moderate rules for maximum results!

References

- Folland, J.P., Irish, C.S., Roberts, J.C., Tarr, J.E., & Jones, D.A. (2002). Fatigue is not a necessary stimulus for strength gains during resistance training. Br J Sports Med, 36(5), 370-374.

- Häkkinen, K., & Pakarinen, A. (1993). Acute hormonal responses to two different fatiguing heavy-resistance protocols in male athletes. J Appl Physiol, 74(2), 882-887.

- Kraemer, W.J., & Ratamess, N.A. (2005). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Med, 35(4), 339-361.

- LaChance, P.F., & Hortobagyi, T. (1994). Influence of cadence on muscular performance during push-up and pull-up exercise. J Strength Cond Res, 8(2), 76-79.

- Mikesky, A.E., Matthews, W., Giddings, C.J., & Gonyea, W.J. (1989). Muscle enlargement and exercise performance in the cat. J Appl Sport Sci Res, 3(4), 85-92.

- Robinson, J.M., Stone, M.H., Johnson, R.L., Penland, C.M., Warren, B.J., & Lewis, R.D. (1995). Effects of different weight training exercise/rest intervals on strength, power, and high-intensity exercise endurance. J Strength Cond Res, 9(4), 216-221.

- Staley, C. (2001, April 28). Russian training philosophy & Schroeder [Message 8271]. Retrieved from http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Supertraining/

- Wernbom, M., Augustsson, J., & Thomeé, R. (2007). The influence of frequency, intensity, volume, and mode of strength training on whole muscle cross-sectional area in humans. Sports Med, 37(3), 225-264.

- Willardson, J.M., & Burkett, L.N. (2006). The effect of rest interval length on bench press performance with heavy vs. light loads. J Strength Cond Res, 20(2), 396-399.

- Young, W. (1992). Neural activation and performance in power events. Mod Athlete Coach, 30(1), 29-31.

From Zero to Two: Leo’s Chin-Up Breakthrough

When Leo began training with me in September 2024, our first goal was to improve body composition — lose fat,

Resistance Training Foundations: How to Progress Safely and Build Real Strength

Resistance training isn’t just for bodybuilders. Whether you’re just starting out, returning after a break, or training for performance, knowing

Neck Extensions Before Arm Curls: Unlock More Strength

When most people warm up for arm curls, they’ll hit a few light sets or maybe stretch out a bit.

follow

Error: No feed with the ID 2 found.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.