As you hit your 40s, 50s and beyond, you realize that you are no longer able to do what you did in your late teens, 20s and even early 30s. Weights that used to feel like feathers start to feel more like boulders. Loads that were once part of your warm-up sets, all of sudden become your work sets. It’s inevitable – just part of aging, I guess. But just because the loads may drop a bit, it doesn’t mean that your overall strength and size need to plummet. It just means that you have to work smarter, not necessarily harder!

When middle age hits, moderate rules should be followed, i.e., use a moderately-heavy weight, for a moderate number of sets and repetitions, at a moderate pace, and with moderate rest intervals. You look at that and say: “Okay, a typical bodybuilding scheme. I can follow that, no problem.”

Then you set off to the gym to workout. You know that you’re supposed to keep a training log and sure enough, you’ve got one! Everything is outlined for the day – what exercises you’ll be performing, their sequence, and all the other variables are there too, including sets, reps, tempo and rest interval.

Everything is perfect… on paper, that is. As soon as you start training, two of those variables get thrown out the window. You know which two!

Time Is More Important Than Load

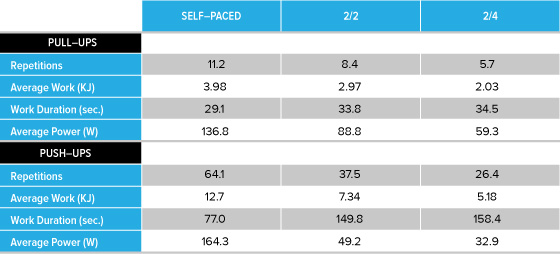

One day I had a serious revelation – you may even call it an epiphany. It happened while reading a research paper by LaChance & Hortobagyi (1994) titled “Influence of Cadence on Muscular Performance During Push-up and Pull-up Exercise.” The study was based on 75 moderately-trained college-age men who were tested over 6 days for the maximum number of repetitions during push-ups and pull-ups at each of 3 cadences: fast self-paced, 2/2 (2-second concentric phase followed immediately by a 2-second eccentric phase), and 2/4 (2-second concentric phase, 4-second eccentric phase). For both exercises, results showed that faster cadences permitted significantly more repetitions, greater work, and higher power outputs than slower cadences. It was pretty clear that exercise cadence, often referred to as tempo, influences muscular performance.

Now if you read the abstract alone, you would think that a self-paced cadence is a superior method of training. Well, not so fast, literally and figuratively! Let’s take a closer look at the results and see if you feel the same way after you go through the actual numbers.

(from LaChance & Hortobagyi, 1994).

When push-ups were performed at a 2/2 cadence as opposed to a self-paced cadence, the reps dropped almost in half, but the work duration (i.e., the time under tension) more than doubled. Of course, the 2/4 cadence decreased the number of repetitions further, but the work duration was even higher than the 2/2 cadence. A similar pattern occurred on pull-ups although not as dramatic.

And why is work duration important?

To answer that question, we need to go back a few more years to a paper published in 1989 in the Journal of Applied Sport Science Research. A team from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas conducted a very interesting study. They analyzed 156 training variables for exercise-induced increases in muscle mass in cats. Seventy-seven cats were used for the study (62 exercised and 15 were controls). The exercised cats trained their right palmaris longus muscle (PLM) by performing a wrist flexion movement against resistance, while the left PLM served as the non-exercised intra-animal control. The cats trained 5 days per week and after an average of 90 weeks (the study actually ranged from 30 weeks to as much as 311 weeks, almost 6 years), the left and right PLMs were removed and weighed.

The variable which demonstrated the highest correlation to increases in muscle mass was the lift time. Next on the list was the amount of weight lifted. Basically, slow lifting movements with relatively heavy weights resulted in the greatest muscle mass gains. According to the researchers, “The slow lifting style may minimize the role that momentum plays in completing the lift, thereby maintaining the need for tension development throughout the range of movement.” As long as the stimulus was sufficient (i.e., a slow, heavy lift) and progress was made over time, muscle mass increased. However, the paper did indicate that a critical level in the amount of weight lifted was necessary for hypertrophy. In this particular study, it was a minimum of 30% of the cat’s body weight.

And for humans, the mega 39-page review by Wernbom et al. (2007) titled “The influence of frequency, intensity, volume and mode of strength training on whole muscle cross-sectional area in humans” showed that performing sets to failure with moderately-heavy loads (i.e., intensities above 60% of 1RM with highest rates occurring around the 70-85% of 1RM mark) yield the greatest results. The review clearly indicated that maximal loads are not necessary for hypertrophy, but training should be performed close to maximum effort in at least one set. It also implied that the total duration of muscle activity per session may be a more critical factor than the total reps in terms of the volume required to induce hypertrophy. As stated in the paper: “Based on the available evidence, we suggest that the time-tension integral is a more important parameter than the mechanical work output (force x distance).”

Sure, we may not be cats and we may not be training our PLMs 5 days a week, but it seems reasonable to assume from the evidence presented above that a certain amount of tension and a certain duration of tension is required for hypertrophy.

How much of each is the million-dollar question?

As far as the amount of tension: not too high and not too low. A moderately-heavy load of 70-85% of 1RM, or a weight that allows you to achieve between 5 and 12 reps maximum, is best.

As far as the duration of tension: not too long and not too short. A moderate pace of 4 to 6 seconds per repetition with a time under tension that ranges from 20 seconds (4 seconds x 5 reps) to 72 seconds (6 seconds x 12 reps) per set is best.

Sufficient Not Complete Recovery

The time between sets is another area where too much or too little plays an important role in muscle growth. If you do not rest enough, then of course fatigue will hinder your performance on the next set. But resting too long is not ideal either. The goal is sufficient not complete recovery.

Sufficient recovery occurs when rest intervals reach at least 3 minutes in length. In reality, you should never strive for complete recovery between sets (i.e., more than 5 minutes of rest) because if you wait for fatigue to reach baseline, neural activation will have declined to a point where facilitation is lost for the next set (Young, 1992). Many trainees take longer than optimal rest between sets thinking that recuperation is necessary from the extreme effort, yet it may be more beneficial to take advantage of the neural excitation from the previous set than to wait for fatigue to diminish altogether (Staley, 2001; Weber et al., 2008).

Kraemer & Ratamess (2005) summarize that resistance training protocols high in volume, moderate to high in intensity, using short rest intervals, and stressing a large muscle mass tend to produce the greatest acute hormonal elevations of testosterone and growth hormone (GH) compared with low-volume, high-intensity protocols using long rest intervals. However, significant gains in muscle strength and size can be acquired without the severe discomfort and fatigue associated with short rest intervals (Folland et al., 2002).

The best compromise to avoid a significant decline in performance and yet maximize anabolic hormone production for muscle growth seems to occur when around 3 minutes of rest is taken between sets. Research by Häkkinen & Pakarinen (1993) shows that 10 sets of 10 reps using a submaximal load (70% 1RM) and resting 3 minutes between sets will lead to a significant increase in testosterone and GH levels. In fact, GH increases by twenty-fold, about the same amount that is released early in sleep. Most conventional training programs produce only a ten-fold increase in GH, so this protocol will build muscle and reduce body fat at a high rate. Furthermore, studies by Robinson et al. (1995) and Willardson & Burkett (2006) indicate that 3 minutes of rest between sets allows the use of greater intensities and improves the ability to sustain repetitions resulting in higher training volume and greater gains in muscular strength.

It’s Better To Look Strong Than To Be Strong!

Moderate rules apply to everyone, but they are particularly important as you age: tissue begins to “dry” out; hormones, enzymes and all sorts of things begin to decline; not to mention that responsibilities often change. Being injured when you’re young, energetic and foolish and able to heal fairly quickly doesn’t have as much of an impact as being injured when you’re older and have kids, a mortgage and employment, and the quickest form of healing you’ll experience may be spiritual! You’re not as cavalier as you used to be. Using maximal or supramaximal loads and risk tearing a pec while benching or ruining your back while squatting is unnecessary. Submaximal loads will do just fine, thank you very much!

If you seek size, the recipe for success in strength training is to use enough weight and regulate the time – the time under tension and the time between tension (aka the rest interval). You really do not need massive loads to accomplish the task, moderately-heavy gets the job done. Even Bill Kazmaier, one of the strongest men to have ever walked the planet, has reduced the poundages a bit over the years. As Kaz conceded to Iron Man’s John Rowley: “When you get over 50, you’re better off looking strong than being strong!”

Just remember this: The ladies at the beach don’t care what you lift; they just care about how you look. Young or old, it’s about “time” that you follow moderate rules for maximum results!

References

Folland, J.P., Irish, C.S., Roberts, J.C., Tarr, J.E., and Jones, D.A. (2002). Fatigue is not a necessary stimulus for strength gains during resistance training. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36(5), 370-374.

Häkkinen, K., and Pakarinen, A. (1993). Acute hormonal responses to two different fatiguing heavy-resistance protocols in male athletes. Journal of Applied Physiology, 74(2), 882-887.

Kraemer, W.J., and Ratamess, N.A. (2005). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Medicine, 35(4), 339-361.

LaChance, P.F., and Hortobagyi, T. (1994). Influence of cadence on muscular performance during push-up and pull-up exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 8(2), 76-79.

Mikesky, A.E., Matthews, W., Giddings, C.J., and Gonyea, W.J. (1989). Muscle enlargement and exercise performance in the cat. Journal of Applied Sport Science Research. 3(4), 85-92.

Robinson, J.M., Stone, M.H., Johnson, R.L., Penland, C.M., Warren, B.J., and Lewis, R.D. (1995). Effects of different weight training exercise/rest intervals on strength, power, and high intensity exercise endurance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 9(4), 216-221.

Rowley, J.M. (2012, June 14). Mr. Olympia Samir Bannout on Iron Man Magazine Radio. The John Rowley Show. Retrieved from http://www.blogtalkradio.com/johnrowley/2012/06/14/iron-man-magazine-radio-1

Staley, C. (2001, April 28). Russian training philosophy & Schroeder [Message 8271]. Retrieved from http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Supertraining/

Weber, K.R., Brown, L.E., Coburn, J.W., and Zinder, S.M. (2008). Acute effects of heavy-load squats on consecutive squat jump performance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(3), 726-730.

Wernbom, M., Augustsson, J., and Thomeé, R. (2007). The influence of frequency, intensity, volume and mode of strength training on whole muscle cross-sectional area in humans. Sports Medicine, 37(3), 225-264.

Willardson, J.M., and Burkett, L.N. (2006). The effect of rest interval length on bench press performance with heavy vs. light loads. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(2), 396-399.

Young, W. (1992). Neural activation and performance in power events. Modern Athlete and Coach, 30(1), 29-31.

Stretching Smarter: The Do’s and Don’ts for Maximum Flexibility

By JP CatanzaroOriginally published: September 23, 2014 – Updated for 2025 Want to boost flexibility, prevent injuries, and optimize performance?

Training Economy: How Weight Training Can Be Your All-in-One Fitness Solution

Recent research has once again confirmed what many in the weightlifting community already know: weight training isn’t just for building

4 Invaluable Lessons from Strength Training Pioneer Arthur Jones

Arthur Jones, a true visionary in the realm of strength training, left an unforgettable mark on the fitness industry with

follow

Error: No feed with the ID 2 found.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.