Many myths exist regarding weight training. For instance:

• Weight training will make you muscle-bound and inflexible.

• If you train with heavy weights and slow contractions, you become heavy and slow.

• Squatting below parallel is an invitation for injury.

The list is endless.

None of these are 100% true. Weight training is simply a tool – it’s not the tool that should be blamed, but rather how you use it. Sure, train regularly in a shortened range of motion (ROM) and you may become muscle-bound and inflexible. Constantly training with volitional super-slow movements will not significantly improve athletic performance and may indeed slow you down. Bouncing out of the bottom of full squats is a recipe for injury.

But what if weight training was performed in a proper and appropriate manner? Can we then put these myths to rest? Let’s find out.

A common area of confusion with many personal trainers involves ROM. Do you train in full ROM or not? Well, it depends on the individual and the joint in question. For the most part, you should encourage full ROM – the way our joints were intended to move – but not always. A classic example involves elbow or knee hyperextension.

For instance, ask any bodybuilder to extend their arms out fully, and nine times out of ten you’ll notice that their elbow joints are in a slight state of flexion. Now ask a dancer to do the same, and you’ll typically notice hyperextension at the elbow joints. You may prescribe an arm curl to both individuals, but how they perform the exercise will differ.

The bodybuilder should take advantage of the passive stretch that the weight provides in the bottom position to restore any lost range – in other words, they should be encouraged to train in full ROM. The dancer, however, needs to shorten the range in the bottom position to improve the stability and thus the integrity of the elbow joint. They should be instructed to stop just shy of lock out with a slight degree of elbow flexion at the end of each repetition. The same sort of logic would apply to the knee joint.

The saying “if you train in poor posture, you’ll adopt poor posture” is very true. Another way of looking at it is that if you train in a shortened ROM, you’ll adopt a shortened ROM, and vice versa.

I don’t think people appreciate how powerful of a tool weight training can be to increase flexibility and ROM. An Olympic weightlifter is the second most flexible athlete behind a gymnast. Then again, weight training can also be a powerful tool to decrease flexibility and ROM.

Take the classic muscle-bound bodybuilder who constantly trains in a shortened ROM and thus adopts a shortened ROM (this is where the term “muscle-bound” may be appropriate), but looks can be deceiving and you can’t always judge a book by its cover!

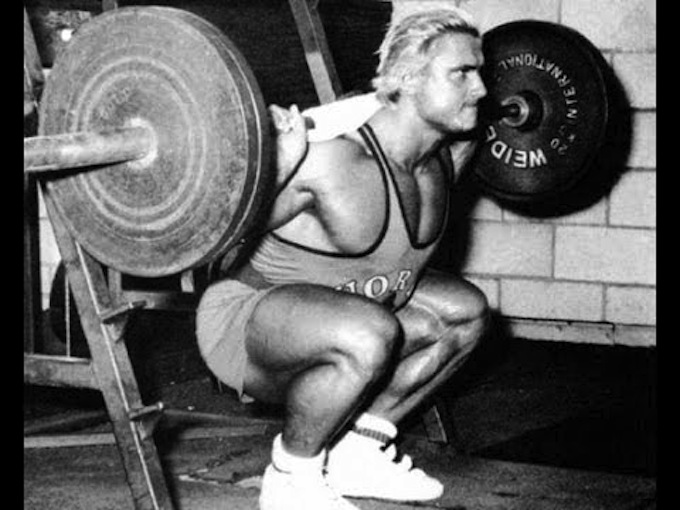

A great example of this is Tom Platz, a professional bodybuilder from the ’70s and ’80s who was known for his extraordinary leg development. Platz routinely performed full squats in his training and could easily touch his toes (actually his head could touch his knees) and do the full splits. Incidentally, if your goal is muscle size, the greater the ROM you train in, the more muscle fiber you stimulate, and thus the greater the potential for hypertrophy. As Platz used to say: “Half squats will give you half legs!”

I’m a big fan of full squats, and typically most new clients have difficulty achieving this position for various reasons:

• tight calves causing the trunk to lean forward

• tight hip flexors causing the heels to raise

• tight glutes which restricts squat depth

• tight hamstrings which causes the lower back to round prematurely

• tight piriformis which causes the foot on that side to rotate outward

• and so on…

The goal over time is to correct these issues and strive for a full squat, which is a normal and healthy position that we are all meant to achieve.

Think of the stability-mobility continuum. If the ankle or hip joint is restricted in a shortened ROM (i.e., less mobility), something will eventually give. Typically, you need to look above or below the joint. In this case, the knees and/or lower back are susceptible to injury. Those that tell you not to full squat and instead advocate partial squats are actually setting you up for injury, not preventing it!

Of course, when such limitations exist, it’s wise to start with easier progressions and work gradually toward the end goal. Initially, I like to use a form of “potty training” that I learned from Dr. Mel Siff.

The Atlantis Step Platform comes in quite useful for this application. Set the step high and have your client sit on it (i.e., squat onto the step). From there, simply get them to stand up. That’s one repetition. Have them squat down again, brush the step, pause, and then back up. That’s the second repetition. Continue until the prescribed number of reps have been performed.

Over time lower the step height and continue the process until a full squat has been achieved. How long this takes will depend on your client, but if you can combine this exercise with stretching of the tight muscles that I listed above on a frequent basis, you’ll speed up the process.

Also, it’s wise to prescribe unilateral training in this situation. A great exercise that will help your full squat efforts is the split squat. This exercise will help stretch the hip flexors, which are considered the most tonic muscles in the human body.

However, the split squat will only help if you encourage full ROM, and for most people to achieve this position initially, you must elevate their front foot onto a step. Just like potty training, over time you can lower the step height until the exercise can be performed

What if you have a situation where your client has too much hip mobility? Again, use weight training as a tool. In this case, I would prescribe a modified split squat where the legs achieve right angles (i.e., a 90-degree bend) at the bottom position. Instead of the front knee traveling forward, the back knee goes straight down, brushes the ground, and then back up to the original position.

This will help shorten and tighten the individual, exactly what you want to do when they’re hypermobile. Too much joint mobility is not good – the joint is lax, lacking integrity and susceptible to injury. Stability is required in this case. Don’t confuse joint laxity with flexibility – they’re not the same!

What goes for the upper body is really no different from the lower body. We’ve been told not to perform a dumbbell or barbell bench press in full ROM – doing so can damage the shoulder joint capsule. This is simply not true if the exercise is performed correctly. Remember Newton’s second law of motion, which states that force equals mass times acceleration – with excessive speeds and/or loads, forces are high and risk of injury increases.

However, with proper form, a controlled tempo and a moderate load, pressing in full ROM is quite safe. In fact, not going to full ROM can be dangerous – certainly not in the acute stage, but chronic pressing in limited ROM can distort posture. Most people present with rounded shoulders, and this form of training can encourage further migration forward and promote deterioration of the shoulder joint and elsewhere.

Whereas, pressing in full ROM and emphasizing the stretched position can counter this condition over the long run. A golden rule to remember is to stretch (lengthen) the short, tight muscles and strengthen (tighten) the long, flaccid muscles.

Don’t get me wrong, I will prescribe a shortened ROM in certain situations with the goal of increasing range over time – but I repeat, “with the goal of increasing range over time!”

What about weight training and athletics? Well, studies that go back as far as the ’50s show a definite benefit of using weight training to improve athletic performance. Athletes have known this all along – they don’t need science to tell them what works. But one area of confusion that still remains to this day involves training speed – one camp states that all concentric actions must be explosive and the other says that it isn’t necessary. This is where science does shed a light, and in a way, both camps are correct.

A classic study conducted in 1993 by David Behm and Digby Sale revealed that the intended rather than the actual movement velocity is what determines the velocity-specific training response. In other words, even if the weight moves slowly (or not at all), the intent to lift fast is important for high-velocity training.

Also, maximum strength training with heavy loads is an effective method for power development. German research has shown that high-intensity weight training (i.e., 1-3 reps with 90-100% of maximum strength) will produce superior results in the rate of force development compared to lower-intensity training. Of course, with loads that heavy the weight will not move fast, but the athlete should send the message to lift as fast as possible to the working muscles.

It’s time to put these weight training myths to rest. We know that exercise is important for health and performance, but people don’t want to waste their time. They want the most for their training buck, and that’s why I’m a big fan of weight training.

Yoga and stretching improve flexibility. Aerobics improve cardiovascular endurance. Pilates will improve core strength, and weight training… well, it will do all of the above and much more! Forget this nonsense that you’ll become heavy, muscle-bound, inflexible, slow and injured with weight training. If you use the tool correctly, you’ll get the proper response.

Introducing Our Electrolyte Formula: Your Workout’s New Best Friend!

Remember those days when a solid workout left you drained, or annoying muscle cramps were stealing your gains? Been there,

4 Invaluable Lessons from Strength Training Pioneer, Arthur Jones

Arthur Jones, a visionary in the realm of strength training, left an unforgettable mark on the fitness industry with his

Enhance Your Sleep Quality: The Simple Sleep Hack of Opening Your Window

Getting a good night’s sleep is crucial for our overall well-being and productivity. Many factors can affect the quality of

follow

Error: No feed with the ID 2 found.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.