Correcting muscle imbalances should be a primary goal when designing strength training programs. For most individuals, a significant discrepancy exists between the shoulder internal and external rotators. Simply put, we do far too much internal rotation in daily activities—and especially during exercise—and not nearly enough external rotation. You should address that in your programs.

Think about how much work you do for the pecs and lats, both internal rotators of the shoulder, compared to the infraspinatus and teres minor, two smaller muscles responsible for external rotation. If these two rotator cuff muscles are weak, they’ll “shut down” the pecs and lats to protect you from injury. That means pressing, chinning, and rowing strength will suffer if your external rotators aren’t up to par. Give them some attention in every program.

Typically, external rotation exercises are placed in the remedial “C” position of an upper-body workout using an undulating periodization scheme as outlined here:

🔗 Periodization for Athletes

Sometimes greater volume (up to 2 exercises per session), frequency (twice a week), and even priority (A or B positions) are required if the discrepancy is quite large.

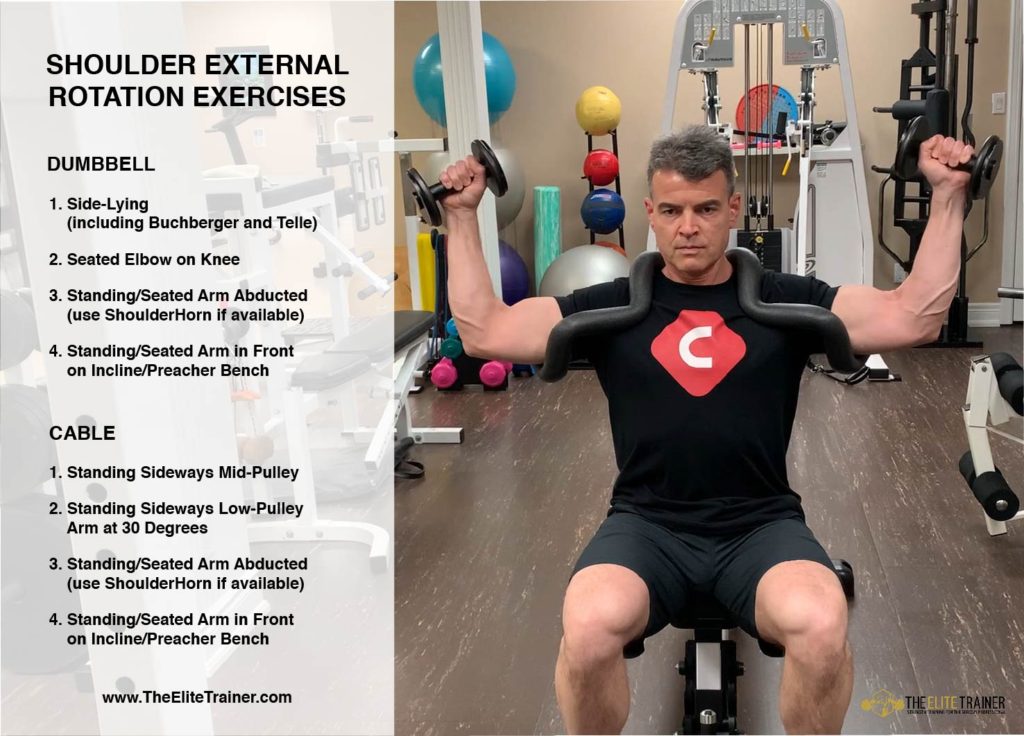

When performing shoulder external rotation, the closer the elbow is to the body, the more the teres minor is involved. The further the elbow is from the body, the more the infraspinatus is engaged. It’s best to vary the elbow position relative to the body in each program. I recommend alternating between dumbbell and cable versions with the arm in the following positions:

Adducted

Abducted 30º

Abducted 90º

Arm in Front

Note: You can alter the point of maximum overload during dumbbell external rotations by adjusting your body position—like in the Buchberger or Telle versions—or by using a prone-incline position. Avoid elastic resistance—learn why here:

🔗 Accommodating Resistance with Tubes & Bands – Part 1

For best results, the upper arm should be supported to increase external rotator activation and reduce involvement of other muscles, especially the deltoids. You can support the arm against your side, on your knee, a preacher bench, an incline bench, or a neat device like the ShoulderHorn. A rolled-up towel under the armpit also works—pressing against it slightly shuts off the medial delts via reciprocal inhibition and boosts infraspinatus and teres minor activation.

🔗 The ShoulderHorn Alternative

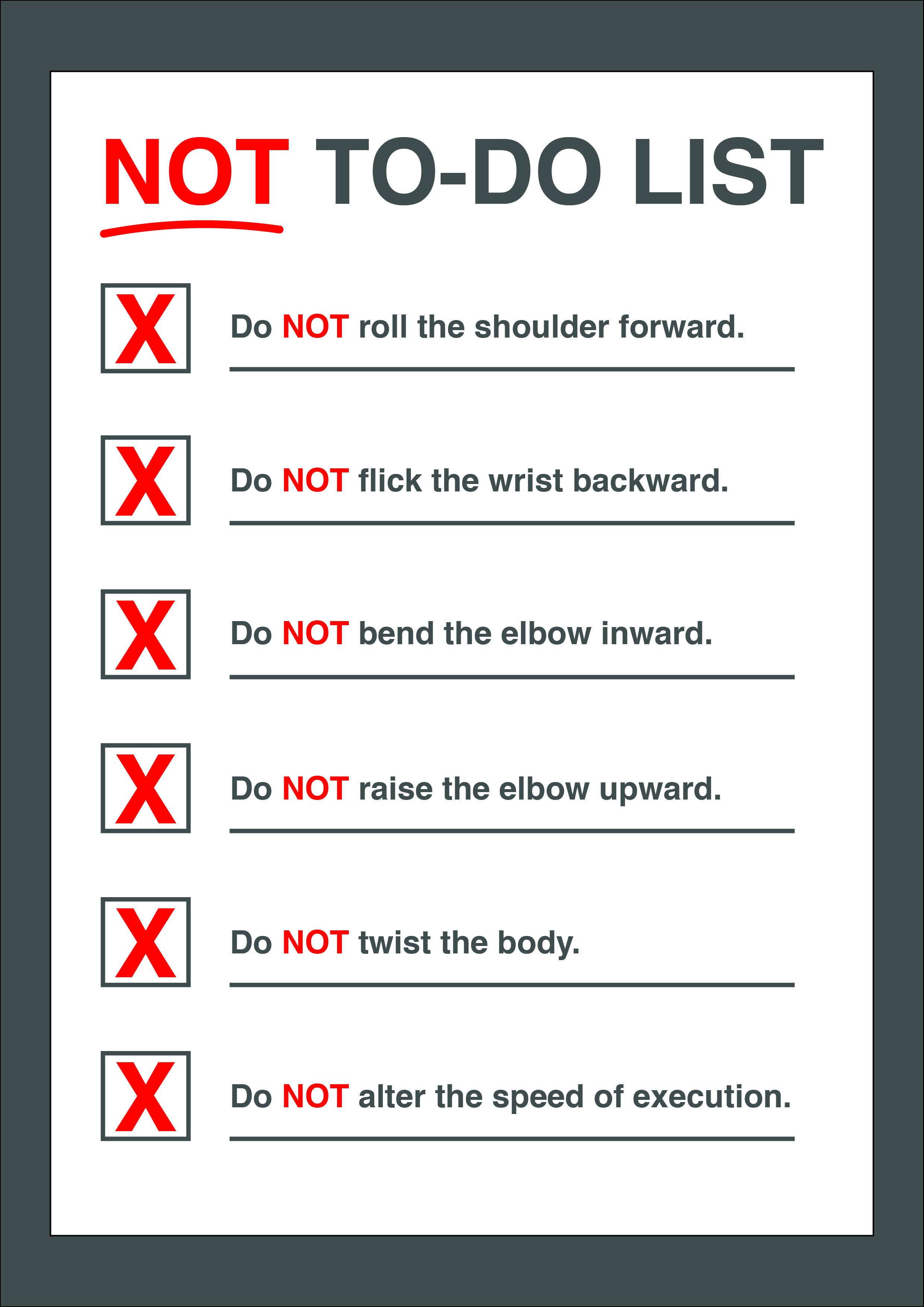

When performing these exercises—or any exercise for that matter—use proper form: set the scapula in a slightly retracted position, keep the wrist straight and firm, maintain a 90-degree angle at the elbow, and rotate only around the shoulder joint.

The infraspinatus and teres minor are small muscles that burn like crazy with higher rep ranges due to lactic acid buildup. It’s easy to cheat. Here’s what you shouldn’t do:

If you notice any of these mistakes, stop! The weight is too heavy. Lighten it up and do the exercise properly. End the set once you lose form. You want to train the right muscles—and avoid learning bad habits. Either do it right or don’t do it at all!

Shoulder external rotation should be a regular part of your training. Two other often weak areas—the rear delts and lower traps—will be covered in a future article.

From Zero to Two: Leo’s Chin-Up Breakthrough

When Leo began training with me in September 2024, our first goal was to improve body composition — lose fat,

Resistance Training Foundations: How to Progress Safely and Build Real Strength

Resistance training isn’t just for bodybuilders. Whether you’re just starting out, returning after a break, or training for performance, knowing

Neck Extensions Before Arm Curls: Unlock More Strength

When most people warm up for arm curls, they’ll hit a few light sets or maybe stretch out a bit.

follow

Error: No feed with the ID 2 found.

Please go to the Instagram Feed settings page to create a feed.